Strengthening The Case For Landmarking Conover House

- Tom Heuser

- Mar 12, 2019

- 14 min read

Though the initial nomination report prepared by Bola Architecture + Planning is well-researched and likely contains enough to convince the board to nominate Conover House, the more we reviewed it and did research of our own the more we realized it had omitted a number of substantial facts and contained some errors regarding the neighborhood and architectural history, Conover's impact on the neighborhood and city, and its physical description. So Rob Ketcherside, Marvin Anderson, Joan Zegree (the former owner), and I used these facts to each prepare our own public comments in favor of nominating Conover House and to set the record straight. As a result, the owner requested to postpone last week's (March 6th) nomination in order to review our comments and respond accordingly. Contained below is a combination of our statements, which contain all that we could find ahead of the March 6th nomination and otherwise point to topics in need of additional research. Based on our findings, we believe that Conover House unequivocally qualifies for landmark status under criteria A, B, C, D, and F and we urge the board to agree with us whenever they get a chance to review it.

Location Location Location.

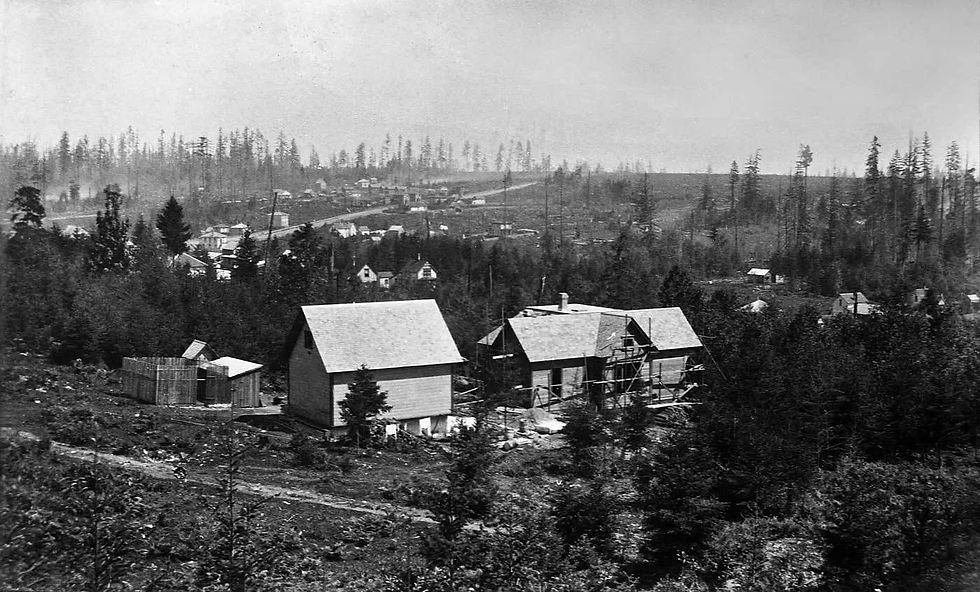

Image: Looking northeast from First Hill toward Renton Hill circa 1890. From pauldorpat.com

First we found that instead of focusing on the immediate surroundings of Conover House, the neighborhood history section of the nomination report focuses exclusively on more distant and unassociated areas that were established much earlier or later such as Denny's Land Claim (1852) and Moore's Capitol Hill (1901). Or in other words, the modern definition of "Capitol Hill" which didn't exist when Conover House was built in 1893. More accurately, Conover House (1620 16th Avenue) is situated on the Madison Street corridor in what is now southeast Capitol Hill bordering on northwest Central District, an area which was previously known as Renton Hill (pictured above). This previous name rose out of “Renton’s Addition” platted by Charles Conover in march of 1889 (in which his house resides) and the adjacent “Renton Hill addition” platted by Sackman-Phillips in 1892 as a part of a transaction brokered by Conover. Both were named after Captain William Renton, the previous owner of the property. An expanded neighborhood history statement would benefit from exploring Renton's connection to the area.

Additional Neighborhood history and Conover's involvement

On Captain Renton's behalf, Conover began developing the area in anticipation of electric streetcar and cable lines that were starting to expand throughout the city. These transit lines promised to make remoter regions more accessible and thus more desirable to future residents. The Madison Street Cable Railway in particular, would allow people to traverse the rough rises and falls between downtown and Lake Washington (then a desirable vacation spot) with relative ease and rapidity and was scheduled to open in June of 1890. However, the Great Seattle Fire struck first in June 1889--just three months after Conover platted Renton’s Addition. As tragic as this event must have seemed, it could not have come at a better time. With money easy to get, the fire drove development in the area even further as existing residents looked to the city’s outer lying regions for new places to live and new arrivals sought opportunities in rebuilding. As a result, the city population increased by half from about 29,000 in February 1889 to 45,000 in May 1890. Transit lines also followed suit. Between the end of 1889 and the end of 1890 cable lines had expanded from 11 to 20 miles and electric rail from 5 to 42 miles. Investors built as fast as they could get rail and wire. The growth after the fire fed on itself.

Image: Two Asahel Curtis photographs stitched together looking toward Renton Hill with Madison street extending northeast from the lower right and intersecting with Union. Circa 1905 according to UW special collections and circa mid 1890s according to Paul Dorpat. From pauldorpat.com

Conover played a leading role both in driving this growth and satisfying the demand for residences by working closely with the Madison Street Cable Railway Company and each ensured the other’s mutual success. After establishing Renton’s addition, Conover went on to plat the Madison Street Cable Railway addition in September of 1892 also situated on Madison just one mile northeast of Renton’s Addition. Using his widely known skills in advertising, he offered the first 10 buyers one-year free passes on the Madison cable car. Lots were bought and developed quickly, guaranteeing customers for the cable car company.

Hereafter and despite the economic downturn of the 1893 panic, Conover went on to be a leading force in the development of east Seattle from Madison Park down to Leschi. He platted and sold several more tracts of land in the area including one that takes his own name “Conover Park” platted in 1907. He originally reserved a large portion of it to be the site for his future home, but later partitioned and sold it off after his wife passed away.

Conover's impact on the city of Seattle and beyond

Conover’s influence reached far beyond this relatively small enclave of Seattle as well. He and his business partner Crawford owned land ranging from fruit orchards in California to mining operations in Alaska and everything in between. In fact, he even platted a tract of land in Ballard called the “Great Northern Addition” in partnership with Frank M Jordan, his notary public in 1890 Advertisements called it the “Pittsburgh of the Northwest”. It is located just a short walk north of the Great Northern Railroad terminal that would later open on Salmon Bay in the heart of Ballard just three years later. The opening of this terminal was a crucial turning point in Seattle’s history and major driver of its growth after the panic of 1893 subsided with the onset of the Klondike Gold rush in 1897.

This and other sources suggest that Conover may have even played a role in the railroad’s establishment here--a point worth exploring further. Through the Seattle Chamber of Commerce (of which he would eventually be a decades-long member) he oversaw the compilation of “Facts and Figures About Washington, the Evergreen state, and Seattle its Queen City” as a gift to James Hill and his associates at the Great Northern Railroad. He later arranged for the display of the products and manufactures of Seattle and Washington at the offices of the Great Northern in St. Paul Minnesota. Aside from Conover’s ties to the Great Northern, the Seattle city council appointed him to a street renaming and renumbering committee alongside city engineer RH Thompson and David Denny in 1892. Up to this point Seattle street names and numbers were in complete chaos and changed from one plat to the next. Initially, Conover used his influence on the committee to pass ordinance 3162 in 1894 renaming the street his house was on from "Joy" to "Renton" to honor Captain Renton, though it didn't hold. His peers overruled him the following year and changed it to 16th through ordinance 4044 which ended the aforementioned chaos and standardized the city's street and numbering system. Conover's other notable accomplishments, activities, and connections

Amersfoort - In 1906 Conover had a sprawling lakeside "Summer home" built for himself and his family just south of Windermere Park. Architects Somervell and Cote, who had come in from New York to assist with the design of St James Cathedral just a few years prior, designed the house. Conover named it "Amersfoort" after an ancestral home in Hollland. Conover sold the house in 1913 and the site would later become the Sacred Heart Villa, a Catholic institution.

Dutch colonial ties - The name Conover is the anglicized form of "van Couwenhoven" a prominent Dutch family of which Wolfert Gerritse van Couwenhoven was the founder of the first European settlement on Long Island, NY called New Amersfoort. Further research is needed to determine Conover's precise connection to Wolfert Gerritse.

30-year mortgage - Standard history has it that the Federal Housing Administration first introduced the concept of the 30-year mortgage in 1934 during the Great Depression after traditional private mortgage insurance providers had largely gone bankrupt. However, a Seattle Times article dated April 24, 1921 claims that Conover himself pioneered the concept and even had it copyrighted at the U.S. patent office. If confirmed, this would change the history of housing as we know it. Further research is needed.

Honorary monument - In 1961, six months before Conover's death, Governor Albert D. Rossellini dedicated a monument with the below quoted inscription and planted a seedling tree in Olympia in honor of Conover.

"A patriot, historian, and writer who dedicated his life to the development of Washington which he named The Evergreen State."

The seedling was from the Lone Tree in Grays Harbor, which served as a maritime beacon ever since it guided Captain Robert Gray into the harbor in 1792.

Architectural Significance and additional ancestral ties

The following is a statement from Marvin Anderson: local architect, historian, and CHHS member.

Conover House is significant as a highly refined - and startlingly early - example of the Colonial Revival style in Seattle. So assured are its proportions and so sophisticated are its details that the house has often been mistakenly dated to early decades of the 20th century when the style had gained broad popularity in Seattle. Instead, the house was built a decade earlier when the Queen Anne and late Victorian styles still reigned, making the Conover house an example that other significant (and landmarked) Seattle homes may have emulated. The building permit for Charles and Louise Conover's house was issued on July 10, 1893 and they moved in later that year, just as the Colonial Revival style was entering into broad popularity across the United States. After the Civil War, architects along the along the Eastern seaboard such as Robert Peabody in Boston and McKim, Mead & White in New York began to document and embrace colonial architecture as America's national style. Widely publicized, their own buildings merged historical recall of colonial simplicity, solidity, and lowliness with Georgian influences and classical detailing to create a new hybrid style dubbed the "modernized colonial." It was a loose approximation of the past, more poetically evocative than historically accurate, adapted to

new taste and requirements. The 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where more than half of the state pavilions were in the "colonial style," proved highly influential to popular adoption of the Colonial Revival just as it encouraged neoclassical architecture in general and gave birth to the City Beautiful Movement. So broadly embraced was this "new" style that by late 1893 critic and architecture professor Howard Crosby Butler echoed many when he wrote, "The Colonial should be our national style; it originated here, is distinctively American, and may be easily adapted to all the requirements of American life."

Charles and Louise Conover would have been well-acquainted with the style even before arriving in Seattle. Born in Esperance, New York, just east of Albany, Charles (1862-1961) was a journalist in Troy and Amsterdam, New York before moving west. Descended from "Dutch colonial stock," his ties to America's history were deep, leading to membership in the Holland Society of New York and to serve as president of the Washington Society of Sons of the Revolution.' Louise Conover (1864-1914, née Mary Louise Burns) also had deep ties to America's past. Descendent of Asa Eddy (1735-1810), who served with the Green Mountain Boys when Ticonderoga was surprised and captured in 1775, Louise was especially close to her grandmother Mary Ann Eddy Faithful, who on her death in 1892 was described by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as "a member of the well-known Southern Ellenwood family, a gentlewoman in the fullest sense, and one of the most brilliant women in Baltimore in her day." Educated, intelligent, and with roots deep in colonial America, Charles and Louise Conover would have been well-versed in the details and character of Colonial Revival architecture well before planning their new Seattle home and popularization of the style by the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

The Conover house on Joy Street (now 16th) just north of Madison has a simple, square form, its hipped roof punctuated by a center gable with fan light. The central bow-front porch is discrete, small even, supported by four turned wood columns, above which is an exquisitely detailed Palladian window illuminating the central stairhall. Four pilasters supporting a denticulated frieze and broad box eave originally divided the front of the house into three equal bays; articulated breaks in the frieze still mark locations of the original pilasters. The well proportioned, rigorously composed front elevation of the Conover house would have been commanding in its presence on the crest of the clear-cut hill and clearly visible from the Madison streetcar, strikingly different and "modern" compared to other nearby mansions, like the 1898 Patrick and Joanna Sullivan house built five years later only one block away.

Like the exterior, the home's interiors were also finely detailed in the Colonial Revival style. Recent real estate photos reveal an intricate stained wood staircase (left image), its fluted square newel posts a classical accent in contrast to the stair's plain paneled wainscot that recalls colonial simplicity. On the upper landing, the interior of the central Palladian window (upper right) is as finely detailed as the exterior (lower right) but with subtle modifications; where the exterior features four slender pilasters dividing the windows - recalling the four larger pilasters that organized the front elevation of the house - trim on the interior is simpler and matches other window casings, uniting the room's interior details. Proportions of the window's denticulated entablatures also differ subtly - the interior appears more finely carved than the exterior, befitting the closer distance from which it would be viewed – while the tops of the entablatures carefully align inside and out.

Fireplace surrounds in the house are likewise carefully studied in their proportion and assured in their detail. Real estate photos reveal three distinctly different fireplaces, their painted wood surrounds still enclosing original glazed tile. Rich in classical detail, these surrounds are nonetheless simple and modern when compared to ornate carved wood interiors found in Seattle's contemporary Queen Anne or late Victorian homes, and would have appeared as such to the many friends and guests entertained by the Conovers.

As interest in the Colonial Revival swept America in the first half of 1893, the Conover's was not the only Seattle house built in the style. On March 27 the Post-Intelligencer reported completion of a seven room "cottage" on Drexel Avenue for George S. Lander designed by J.A. Johnson in "somewhat of the colonial style."l0 In May the P-I announced a new ten-room house "in the colonial style" designed by E.W. Houghton for R.A. Brown on Rose Street, just north of Madison. Two weeks later a large house in Squire park for Albert E. Chaffey was announced: "The style of architecture," wrote the P-1, "is somewhat colonial, although not purely so."And on July 3, just weeks before issuance of the Conover's building permit, a "pleasant cottage" on Madison near Lake Washington for C.W. Kitchen was announced, designed by J.A. Johnson in "the colonial style, with six dormer windows, some of which are circular, and fine bay windows, circular and octagon."13 While these homes, none of which remain, are contemporary with the Conover house and were called "colonial," newspaper accounts suggest they were hybrids, in which colonial and classical details were amalgamated with forms and details of other styles, rather than the finely integrated Colonial Revival style of the Conover house.

Given the influence of Charles Conover in Seattle, the prominence of his new home on Renton Hill, its cost (at $4000 it was among the more expensive homes issued a building permit that year), and the striking, historically accurate Colonial Revival style in which it was built, it is surprising the name of the architect is nowhere to be found. The 1893 Seattle City Directory (pp. 1019-1020) listed 27 architects, many of whom have now faded into obscurity and most of whom could never have designed a home with such accurate and sophisticated detail. But among them was one architect well-versed in Colonial Revival detailing who may have been the architect of the Conover house, James M. Corner. Before coming to Seattle in 1892, Corner (1862-1919) worked for a decade as a draughtsman in Boston. There he published two extremely influential portfolios in collaboration with Eric Soderholtz, Examples of domestic colonial architecture in New England in 1891 and Examples of domestic colonial architecture in Maryland and Virginia in 1892.15 The primary aim of the books, wrote Corner, was "not to accumulate historical data but rather to present in a form convenient for use and reference by architects...some typical examples," to "stimulate closer study in their adaptation to modern domestic work."16 Upon arrival in Seattle Corner partnered for five years with Warren Porter Skillings (1860-1939), who he probably first met in Boston, followed by a better known partnership from 1900-1905 with William E. Boone (1830-1921).17 Extremely artistic and talented, Corner was frequently credited with the design of his partnerships' buildings and is also known to have done work on the side. Whether Corner designed the Conover house will perhaps never be ascertained, but his presence in Seattle guarantees that his books, with their examples of colonial architecture, were known and available as inspiration for design of homes in the Colonial Revival style.

The Conover house is significant to Seattle's history and embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of the Colonial Revival style. Despite modifications over the past century, the house maintains sufficient integrity both inside and out to convey its significance. I encourage the Landmarks Preservation Board to nominate and designate the Conover house a Seattle landmark.

Sources for this statement are available here.

How the Integrity and Historic Value of Conover House Have Been Preserved, 1976-2016 The following is a list of errors and corrections provided by Joan Zegree who owned the house from 1976 to 2016. All errors and corrections are identified by their corresponding page number in the nomination report.

1. Ms. Nellie Standar lived there for 23 years before entrusting me with the keys of ownership. Luckily she avoided some of the avocado and harvest gold decor trends that cycle through interior design, often ravaging historical buildings. The high ceilings, abundance of carved woodwork, hardwood floors, Palladian window and the original glass windows with their bubbles and wavy distortions are a testament to the pre-cookie cutter building aesthetics of the era and have been preserved here. 2. The old oil boiler was decommissioned (page 6), asbestos removed and the oil tank decommissioned. That enabled residents to control heating in each of their rooms with electric baseboards rather than central radiators. Some radiators were left in apartments for historic interest. 3. Each unit was rewired with independent electric meters for equitable billing. 4. I preserved (page 6) the 3 fireplaces’ function by rebuilding the chimneys after the 2001 earthquake. In December 2015, I commissioned new chimney caps for both chimneys, and all 3 fireplaces and flues were cleaned.

5. Correct configuration of apartments (page 6):

Two-bedroom with fireplace, large kitchen, walk in storage

Large studio with fireplace and breakfast nook

1 bedroom with fully finished top floor loft (page 6)

1 bedroom with fireplace, breakfast nook. Apt. does not traverse the entire second story (page 6)

1 bedroom (not a studio, page 6) lower level with private entrance from front of building

Each unit has dedicated walk-in storage in the basement.

6. Re-roofed including new sheathing in 2012.

7. Floors throughout are narrow plank oak (not maple, page 6) and the 4 rooms added after original construction have oak parquet floor.

8. All windows are original wood (page 5) with wavy glass still intact except for one which was cracked when the left mechanism failed. That entire window was rebuilt to original specifications by a professional historic properties woodworker.

9. Denticulated frieze (page 12) on balcony, gable and fascia is still present. There was some deterioration which was restored using custom millwork to replicate the original trim around the balcony.

10. The garden is not simply “… deciduous trees… and grass” (page 4) These evergreen specimens surround the building: magnolia, hollies, camellia, pyramidalis, rhododendrons, azaleas, privet, laurel, variegated yellow hedge. The deciduous trees include several maples including a Japanese maple, lilacs, hazelnut, mountain ash. In addition to “grass” there are roses, daylilies, flax, hosta, Oregon grape, grape hyacinth, native ferns and myriad other perennials.

11. Garden and common areas were maintained with weekly service.

12. Low flow toilets installed in 2016: a 21st century newfangled addition.

13. Annually, maintenance, repairs and any issues of preservation and aesthetics were addressed.

14. The original (page 6) exterior narrow wood siding remains under the siding tiles in place currently.

15. Kitchens retain built-in breadboards, tilt-open flour bins and vented pantry cabinets.

16. The attic became a finished loft, initially used by a renowned Cornish dancer and choreographer and then for photography, fine arts and tech home studios.

17. No evidence of “wide corner trim” (page 6) on 1937 photo, only the original decorative wood pilasters at the corners.

18. In addition to the shutters on the 4 front windows (page 5), there are shutters on the single story addition in the southeast wing and the lower unit.

19. There is a gate on the southeast walkway to the back with an arched arbor for a climbing rose.

20. Genuine linoleum has been preserved and where the original was beyond repair, removed and covered with a new version of classic linoleum, Marmoleum. 21. The likely original kitchen (the southeast “L”) floor had been covered with linoleum and when it was beyond repair it was removed and the original narrow plank wood floor was sanded and refinished.

22. The southeast wing was the original “L” in the footprint as shown on the Sanborn 1893 map. Therefore changing the footprint to a U could not have occurred as described on page 9.

23. Alley behind house is gravel (page 4) except for the short distance from 16th Ave to the JFS driveway.

24. It seems possible that the ‘sleeping porch’ described in county records of 1914 is related to the small two-bedroom single story addition on the southeast corner with fixed windows and ventilation louvers. In that 2-bedroom addition on the main level and the one bedroom apartment on the lower level, there was a clever use of louvers to the outside to admit fresh air into the rooms without the need to open the windows. The windows (page 6) are fixed. Charmingly, the three closets in these three bedrooms are lined in fragrant cedar siding, and when sanded slightly the scent is still there: a whiff of a century-old past!

**CHHS relies on donations from supporters like you! Donations cover our research costs, cloud storage, website hosting fees, and more. Consider making a donation at capitolhillpast.org/donate**

Comments